Here are the notes based on the talk by Dr Jankharia. There are a couple of links as well at the end to read more from, and links to two ppts put up on this topic on slideshare by Dr Jankharia sometime back (they have more images to refer to). We haven’t put a lot of images into the notes; we suggest reading the notes with the slideshare open in another tab to look at relevant images, and then finish it off by reading the two pdfs.

SCANNING TECHNIQUE

1. Obtaining good quality HRCT images is an essential step for evaluating pulmonary pathologies. A major problem in India regarding thoracic CT imaging is suboptimal quality of the scans due to the patient not having received adequate instructions regarding taking a deep breath and holding it for the duration of the scan. Proper counseling of the patient prior to the CT even by paramedical personnel significantly improves patient compliance and scan quality, and is mandatory. The technician/ancillary staff must always demonstrate to the patient how to take a deep breath and hold it, and explain that the instructions will come from the machine via a recorded voice so that the patient is not startled. Similarly, how to exhale and hold ones breath for the expiratory phase must also be separately explained, and the patient must understand the timing of this happening.

2. A common imaging conundrum when the CT is not obtained in maximum inspiration is the appearance of reticular opacities in the gravity dependent segments of the lung, especially at the lung bases. These can be confirmed as ‘dependent densities’ and not a more sinister pathology by repeating a CT of the patient in the prone position. The patient should be made to lie on the CT table in prone position for 5 minutes for the dependent blood flow to normalize and the densities to vanish, before repeating the CT.

3. One way to confirm whether the CT has been obtained in inspiration or expiration is by observing the contour of the trachea. The trachea is round and expanded in inspiration, and collapsed and crescent shaped in expiration.

4. Proper lung window width and window level settings are a must for evaluating and filming pulmonary pathologies adequately. A useful pointer to check whether the window level and width are appropriate is that the interfaces between the lung, pleura and rib should be well seen.

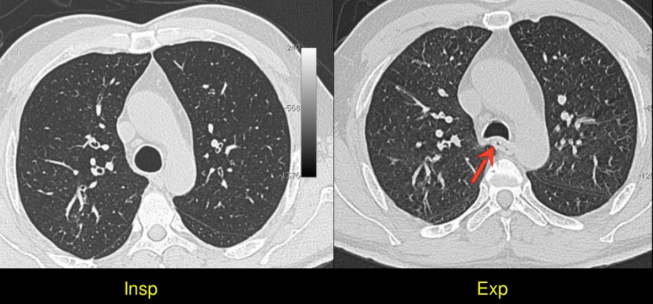

5. HRCT images should always be obtained in maximum inspiration as well as in end expiration.

APPROACH TO DIAGNOSING ILD

6. One must note the presence or absence of nine findings on the CT to diagnose interstitial lung diseases. The ILDs will usually be easily diagnosed based on the combination of these nine findings along with associated history. These nine findings are

- Reticular opacities (described ahead)

- Traction bronchiectasis

- Honeycombing (described ahead)

- Ground glass opacities

- Consolidation

- Septal thickening (interlobular)

- Cystic ILD

- Ill-defined nodules (described ahead)

- Well-defined nodules (described ahead)

7. Having appropriate history is of paramount important. It is important to understand that the lung responds to insult (be it infection, inflammation, allergy, vasculitis, fluid overload etc) in a finite number of ways, giving only a finite number of patterns on CT (listed above). Thus, many different interstitial pathologies may appear similar on imaging; history is the only way to differentiate between them. Age, history of smoking, history of connective tissue disease, exposure to allergens (having pets for example), occupational history etc are all important.

SECONDARY PULMONARY LOBULE

8. It is important to understand the anatomy of the secondary pulmonary lobule and interlobular septum. The figure explains this beautifully (Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, from https://radiopaedia.org/cases/8760, rID: 8760</a>).

Note that the interlobular septum contains only vessels and lymphatics. Thus, interlobular interstitial thickening is usually seen due to pulmonary edema/pulmonary vein compression or stenosis, leading to backpressure changes and fluid retention within the septae; or due to cells (tumor cells in lymphangitis; proteins in alveolar proteinosis) within the septum.

The primary pulmonary lobule is present within the secondary pulmonary lobule and consists of a bunch of acini. Intralobular insterstitial thickening (at the level of the primary pulmonary lobule) is seen in the form of reticular opacities.

FIBROSING ILDS

9. The first step in evaluating for ILD is to distinguish between fibrosing and non-fibrosing ILDs. The presence of reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing indicates fibrosing ILD; namely UIP, NSIP, or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

- Reticular opacities are usually subpleural ground glass opacities and happen at a level within the secondary pulmonary lobule. They indicate the presence of intralobular septal thickening (as against the conventional ‘septal thickening’ which is interlobular).

- Fleishner Society defines radiologic honeycombing as ‘clustered cystic air spaces, cysts of comparable diameters, and cyst diameters typically <10 mm surrounded by well-defined walls’. Honeycombing would present as pleural based rows of cysts stacked one upon the other, with the walls of the cysts in contact with each other (see figure below). These usually begin at the bases posteriorly but then will track anteriorly as well. You can read more on honeycombing at http://err.ersjournals.com/content/23/132/215.

10. Remember; CT has a high specificity but low sensitivity for diagnosing UIP. This is because UIP can present in a variety of ways other than the classic UIP pattern (i.e. presence of honeycombing on HRCT). Importantly, usual interstitial pneumonia pattern without a known cause is termed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which has a very poor survival and is like a death sentence. It must hence be diagnosed only when CT unequivocally indicates this diagnosis.

Classification of findings in a fibrosing ILD seen on HRCT:

11. Once you see a fibrosing ILD, it should be classified as one of the following patterns. (Details on table 4 of the evidence-based document on IPF in the link at the end).

- UIP pattern: This diagnosed when there are reticular opacities and honeycombing, with or without traction bronchiectasis. There should be a subpleural basal predominance with lack of the ‘inconsistent with UIP’ features. ‘Propeller blade” distribution pattern may be seen. This name is derived from the fact that the honeycombing or reticular changes move from being predominantly posterior to anterior as we move on sequential axial images from caudal to cranial. The diagnosis in these cases is unequivocally UIP.

UIP pattern. CT showing reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing. (Image from Wikimedia Commons; contributed by Darel Heitkamp, MD.)

- Possible UIP: There are reticular opacities in a predominantly subpleural basal distribution without honeycombing, and in the absence of ‘inconsistent with UIP’ features. Differentials in this case would be UIP and NSIP.

- Inconsistent with UIP: There are features seen on the CT which are not classic of UIP. These include presence of air trapping or mosaic appearance, ground glass opacities, upper or mild lobe predominance, diffuse micronodules, peribronchovascular abnormalities, multiple cysts, or consolidation. Differentials include chronic fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (amongst others) and rarely atypical IPF.

- Thus note that UIP/IPF can present on HRCT with all four patterns, including rarely with the ‘Inconsistent with UIP’ pattern as well.

12. UIP vs NSIP:

- If the pattern is not classic for UIP and NSIP is a differential, few pointers help. An older patient with age > 70 years is more likely to have UIP, whereas a younger patient with age < 50 years is more likely to have NSIP.

- Presence of a connective tissue disease almost always indicates NSIP.

- Regression following treatment with steroids is seen in NSIP and not UIP.

- If there is any clinical doubt, a follow-up CT or a biopsy should be performed.

NON-FIBROSING ILDS

13. If the diagnosis is of a non-fibrosing ILD, the presence of the combination of other findings on HRCT can help make the diagnosis.

14. If the only finding is the presence of ground glass opacities, there are multiple differentials.

- RB-ILD or DIP if there is history of smoking

- AIP (ARDS) if the patient is having respiratory failure and is on ventilator

- PCP infection if the patient is HIV positive and has a low CD4 count

- NSIP if there is connective tissue disease

- Pulmonary edema if associated with effusions/septal thickening

- Acute/subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis if there appropriate history of allergen exposure. If there is no obvious history, this still remains as a differential.

- If we do not know the history (apart from the obvious AIP or pulmonary edema), the impression can be worded as ‘This findings can be seen in RB-ILD or DIP if the patient is a smoker. Assuming that the patient is not a smoker and is not immunocompromised, the differentials would include hypersensitivity pneumonitis and NSIP.’

15. Consolidation is the defining feature of only one interstitial lung disease: organizing pneumonia. This may have a known etiology (e.g. drug-induced); when the etiology is unknown, it is called cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Other diseases which can mimic the organizing pneumonia pattern on HRCT (present as consolidative opacities) are:

-

- Infective pneumonia

- Bronchoalveolar carcinoma

- Lymphoma

- IgG4 disease

- Vasculitis

16. Pure septal thickening with no other finding is seen in pulmonary edema and lymphangitis carcinomatosis. Lymphangitis classically presents as nodular septal thickening, but it may be smooth as well. Pulmonary edema is usually easily diagnosed based on the presence of dependent smooth septal thickening along with effusion/s, and associated clinical history.

17. Cystic ILDs include Langerhan cell histiocytosis (LCH), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), Birt Hogg Dubbe syndrome, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and rarely cystic metastases from angiosarcoma. Usually, in a cystic ILD, the intervening lung parenchyma is relatively nomal (LCH may be an exception).

18. Note that the cysts in cystic ILD will have walls. Cysts without wall indicate emphysema. Cysts with a discernible wall may represent cystic ILD as also other differentials such as bronchiectasis, honeycombing, cystic metastases, septic emboli etc.

19. Nodules: Note that ‘bronchocentric’ nodules is the new term for ‘centrilobular’ nodules. Nodules should be considered well-defined if they can be clearly delineated, and ill-defined if not. Sometimes, multiple tiny well-defined nodules may coalesce and appear as ill-defined opacities, confusing us (may happen in military TB). Acute/subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a common disease which may present with ill defined bronchocentric nodules, as also ground glass opacities.

20. Once the presence of the various HRCT findings is jotted down, the combination of these findings along with appropriate history helps clinch the diagnosis or appropriate differential. For example, a combination of ground glass opacities + septal thickening (crazy paving pattern) is seen in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.

More information:

i. Dr Bhavin Jankharia has shared his ppts on HRCT in diffuse lung diseases (parts I and II) on slideshare. Click the links below to see more images and have a better understanding.

https://www.slideshare.net/bhavinj/hrct-in-diffuse-lung-diseases-i-techniques-and-quality

ii. There is an excellent article on radiographics on the ILD classification.

http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.2015140334

iii. The official statement for evidence-based guidelines and management of IPF: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL

– Ameya Kawthalkar, Senior registrar, Tata Memorial Hospital

– Akshay Baheti, Assistant Professor, Tata Memorial Hospital