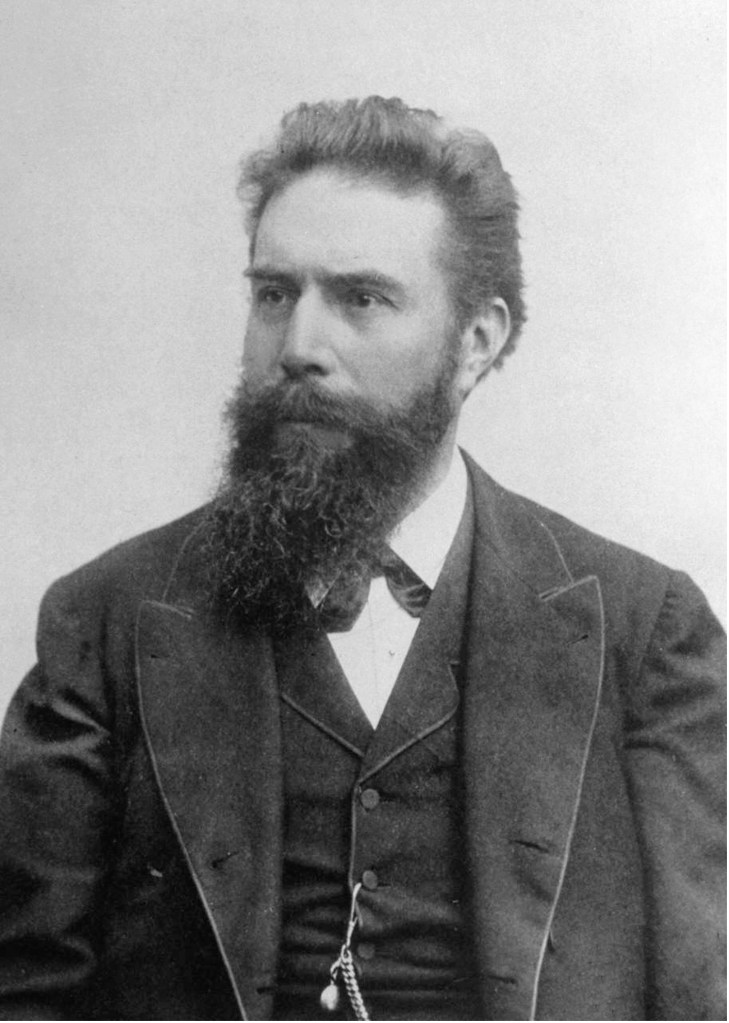

Wilhelm Roentgen (or Röntgen in German) is a name we’re all familiar with, even if our pronunciation of his name might differ from that in his native German. The father of radiology, as he is rightfully known, has truly left an indelible legacy in the world of science and medicine. His pioneering work with X-rays in the late 19th century laid the foundation for modern medical imaging. Beyond the accolades and the fame that he received, his story represents the essence of curiosity, dedication, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge that continues to inspire people around the world.

Roentgen’s legacy is truly remarkable, stretching across disciplines, generations and geographical boundaries. The fact that we are discussing his legacy on Café Roentgen, a platform named in his honour, is a testament to the enduring impact of his work. The logo of Café Roentgen features a hand radiograph (complete with the ring), holding a radiopaque cup with “Café Roentgen” written on it in a font reminiscent of the film The Godfather. It is therefore appropriate that we first talk about the (God)father of radiology, and two hand radiographs (with rings) that he famously captured.

Wilhelm Roentgen’s Background

Roentgen was born in 1845 in a small German town named Lennep (now part of the city of Remscheid, near Cologne), and moved shortly afterwards to Utrecht in the Netherlands, where he attended school. He was unfortunately expelled from high school when one of his teachers intercepted a caricature of one of the other teachers that he reportedly did not draw. Struggling to find a college that would accept a candidate without a high-school diploma, he eagerly seized an opportunity to study mechanical engineering provided by the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich, and moved to Switzerland. He eventually graduated with a PhD from the University of Zurich and moved back to his home country – as a faculty member first at the University of Strasbourg, followed by the universities at Giessen, Würzburg and Munich.

In 1895, while working at the University of Würzburg, Roentgen was studying various kinds of vacuum tubes, focusing on what happened when electrical discharges travelled through these tubes. In early November, while working on a Lenard’s tube (a kind of vacuum tube made of thin glass), he noticed that some invisible rays caused fluorescence on a cardboard screen coated with barium platinocyanide, placed near the aluminium window. This intrigued him to consider whether the Crookes-Hittorf tube, with thicker glass walls, could produce a similar effect.

On the fateful afternoon of 8 November 1895, Roentgen connected the Crookes-Hittorf tube to a pair of electrodes and dimmed the room. To his astonishment, he observed a faint shimmering image of a nearby bench each time he discharged the tube. Further experiments over the weekend confirmed his suspicion of a new type of rays. Naming them “X-rays” (with “X” representing the unknown), Roentgen dedicated himself to their study, and in this process captured the first radiographic image — a flickering silhouette of his own skeleton, an image that is unfortunately lost. Around six weeks after his groundbreaking discovery, Roentgen captured another radiograph – this time of the hand of his wife, Anna Bertha. When she saw the silhouette of the skeleton of her hand, she remarked, “I have seen my own death.”

Anne Bertha and the Radiograph of Her Hand

Wilhelm met his wife Anna in 1866 in Zurich, at “Zunfthaus Zum Grunen Glas” (The Green Glass Guildhouse), a café run by Anna’s father. They got married six years later, with lots of reservations from Wilhelm’s father, who was unhappy that his son was marrying a woman from a very humble background who was also six years older to him. They never had any children of their own, but adopted a little girl named Josephine, the daughter of Anna’s brother – after his unfortunate demise. She suffered from renal issues for years and died at the age of eighty years.

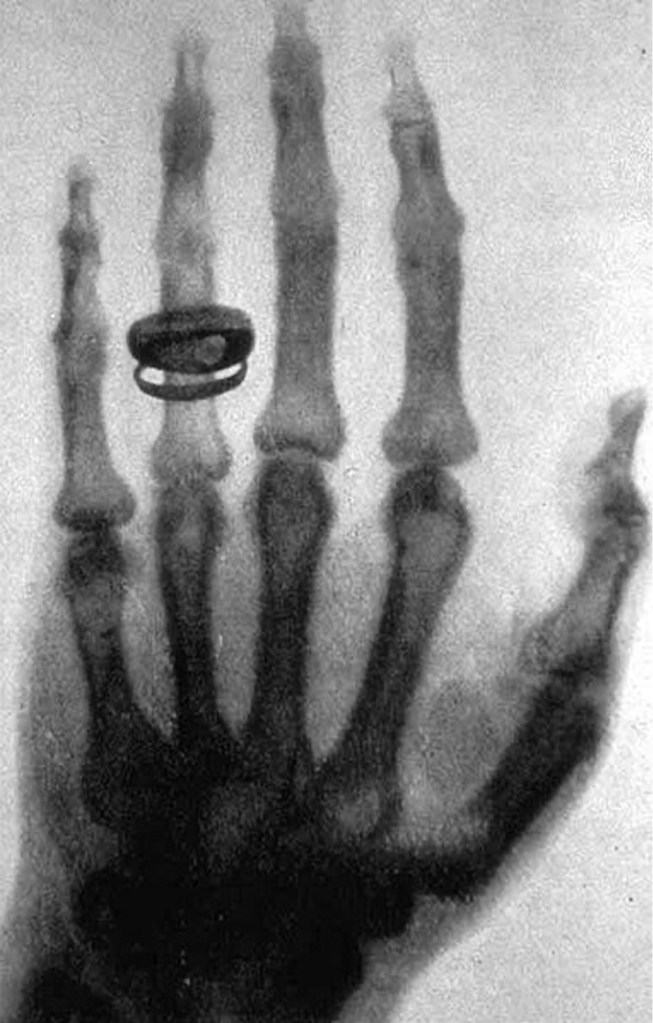

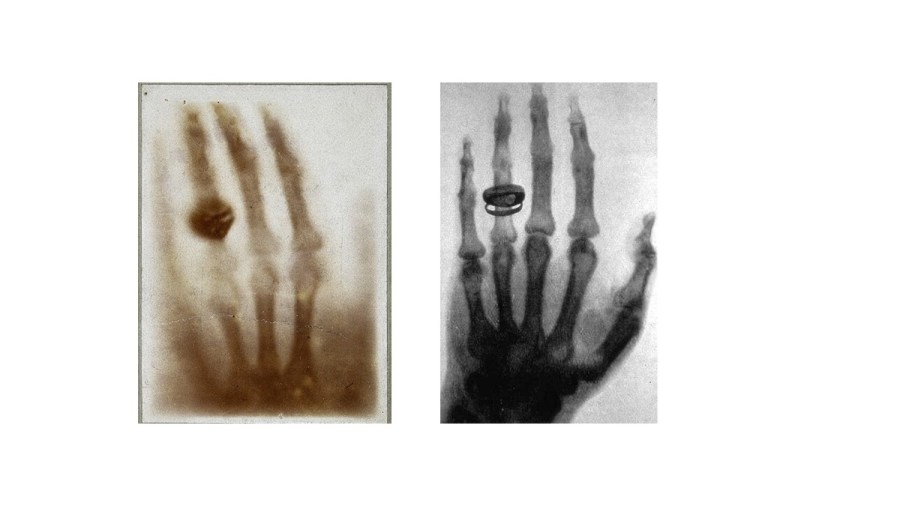

Anna’s hand radiograph, a part of Roentgen’s personal collection, is truly iconic, to say the least. It’s a fuzzy image that shows the bones of her hand, and the ring that adorns it. Countless radiology professionals have seen this image, making it perhaps the most defining emblem of the field. This radiograph marks a seminal moment in medical history, and Anna’s contribution to the world of radiology remains invaluable.

But there is another radiograph captured by Roentgen that is often confused with this one, and that too has an interesting story associated with it.

Albert von Kölliker

Born in 1817, Albert von Kölliker was a Swiss anatomist best known for discovering the mitochondrion – the powerhouse of the cell. He was also the first person to demonstrate that smooth muscle is made of many small nucleated muscle cells, and that nerve fibres are continuous with nerve cells. His impact on the world of biology is truly immense. As a professor at the University of Würzburg, he shared academic space with Roentgen, his close friend and colleague.

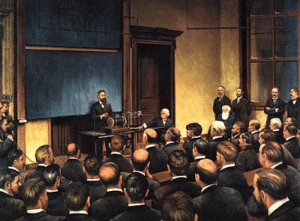

On 23 January 1896, he was in the audience for a lecture by Roentgen on his recent discovery, who had been invited by the Physical-Medical Society of Würzburg for a talk. This would be the only public lecture that Roentgen would ever take on X-rays. During the lecture, Roentgen called von Kölliker to the stage as a volunteer and captured a radiograph of his hand. Amazed by what he saw, von Kölliker suggested the unknown rays be called “Roentgen Rays”. The audience agreed in a standing ovation.

Roentgen’s radiograph of von Kölliker’s hand marked a significant advancement in the nascent field of radiography. This image represented a refinement compared to the earlier radiograph of Anna’s hand. In the weeks following his discovery, Roentgen diligently refined and fine-tuned the technical aspects of the imaging process. His meticulous adjustments led to significantly enhanced clarity, allowing him to capture the more intricate details of the anatomy of von Kölliker’s hand. This showcased the potential of X-ray technology for medical diagnostics, highlighting specific bone structures and nuances previously invisible to the human eye. The radiograph of von Kölliker’s hand not only demonstrated Roentgen’s mastery of the X-ray technique but also demonstrated the scope for future advancements in the field of medical imaging.

Back to Roentgen

Wilhelm Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895 truly revolutionized the landscape of medicine, opening a realm of diagnosis and exploration previously unimaginable. The ability to see inside the human body without invasive procedures transformed medical practices, enabling doctors to diagnose all kinds of diseases. Roentgen’s pioneering work with X-rays was quickly recognized, earning him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 (the first year the Nobel Prizes were given out), a testament to the profound impact of his discovery on the scientific community. Remarkably, Roentgen chose not to patent his radiographic technique. Instead, he selflessly shared his findings with the world, encouraging researchers to better it, ensuring that X-ray technology rapidly spread across the globe without financial barriers.

Roentgen passed away at the age of 77 on February 10, 1923, succumbing to colorectal cancer in Munich, Germany. His demise marked a profound loss for the medical community. His enduring legacy lives on, not only in the multitude of lives saved through early and precise diagnoses facilitated by various imaging techniques but also in his spirit of scientific generosity – a spirit that continues to inspire researchers to this day.

In closing, I’ll leave you with the following link of the café where Wilhelm Roentgen met his wife, Anna Bertha. It still survives today, as a fine-dining restaurant. If there is any actual physical establishment in the world that could potentially call itself “Café Roentgen”, it’s this one. Do visit it if you ever find yourself in Zurich – I know I will some day!

– Dr Anmol Dhawan

Dr Anmol Dhawan is a radiologist working as a senior resident at Bharati Hospital, Pune. He enjoys writing about radiology, history and culture. You can check out his blog at https://syndrome.home.blog/ and you can reach out to him at anmoldhawan@gmail.com.

Great stuff! Very intriguing to read about the one radiograph seen by almost everyone in the radiology community!

LikeLike

Amazing content!! Keep it up 👍

LikeLike

Incredible article about a landmark moment for mankind in treating itself. The biggest takeaway of this is that Roentgen refused to build his wealth upon this discovery after realising the lifesaving potential it had. That makes him stand out to me as someone who pushed mankind forward for the greater good, unlike the many who claim to do so as a facade for gaining more wealth.

LikeLike

A wonderful read on a lazy Sunday.. keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Such beautiful writing this is. I appreciate your talent.

LikeLike

Very well written. Thanks Dr Anmol

LikeLike

I think the effects on those who regularly used radiology as a diagnostic tool were not well understood in the beginning. Little precaution was taken initially to protect radiologists from the potential harm directing the use of this wonderful diagnostic medium on a daily basis without adequate protection.

LikeLike