Have you ever used a vinyl record? If you’re a fan of vintage music formats, you might enjoy the nostalgia or the tactile experience of spinning a vinyl record on a turntable. But did you know that in certain parts of the world, during times of cultural and political repression, people had to make do with all sorts of unconventional materials to create their own DIY records? One of the most fascinating examples of this is the use of X-ray films as a substitute for vinyl in making records. This is the story behind it.

How It All Began

In 1877, Thomas Edison invented the gramophone – the first device which could both record and reproduce sound. The idea was simple, yet remarkable – his device recorded sound by indenting grooves onto a cylindrical tin foil using a stylus vibrating with sound waves, while playback involved the stylus tracing these grooves to reproduce sound, amplified by a horn or speaker.

Ten years later, Emile Berliner patented his version of the gramophone, which used a flat disc as the medium for recording and playback instead of Edison’s cylinders. In this version, the stylus moved laterally across a rotating disc, cutting a spiral groove into the disc surface, with the playback mechanism largely similar to Edison’s machine.

The use of flat discs had several advantages over cylindrical recordings. Discs were easier to mass-produce, allowing for more efficient distribution of recorded music. Additionally, the flat disc format enabled longer recordings to be made on each side compared to cylindrical records, which had limitations due to their smaller size. It was Berliner’s gramophone which popularised the disc format and laid the groundwork for the modern record industry.

Until the 1940s, the primary material used for making discs was a substance called shellac, a resin secreted by the female lac bug on trees in the forests of India and Thailand. Shellac was also used to produce explosives and its demand for this purpose skyrocketed in the early years of the Second World War. The War Production Board under President Franklin Roosevelt ordered a 70% cut in the production of new records. In addition, the US government released posters asking citizens to donate old records to recycle them and extract shellac. Around this time, the US Armed Forces experimented with a plastic substance called polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to produce records for use by overseas troops. PVC proved to be a better material for pressing records due to its light weight as well as its smoothness, which minimised friction between the record grooves and the needle. Soon, PVC replaced shellac as the medium for record discs, and that’s how we get the term “vinyl record”.

From the 1950s onwards, vinyl records experienced a meteoric rise in popularity, becoming the dominant medium for listening to music in households worldwide. Throughout the following decades, vinyl records served as the cornerstone of music culture for music enthusiasts around the world.

Back in the USSR

As the euphoria of the victory of the Allied Forces in the Second World War gave way to the tensions of the Cold War, the Soviet Union tightened its grip on Western music and art, forbidding the import of what they felt was decadent and culturally corrosive material.

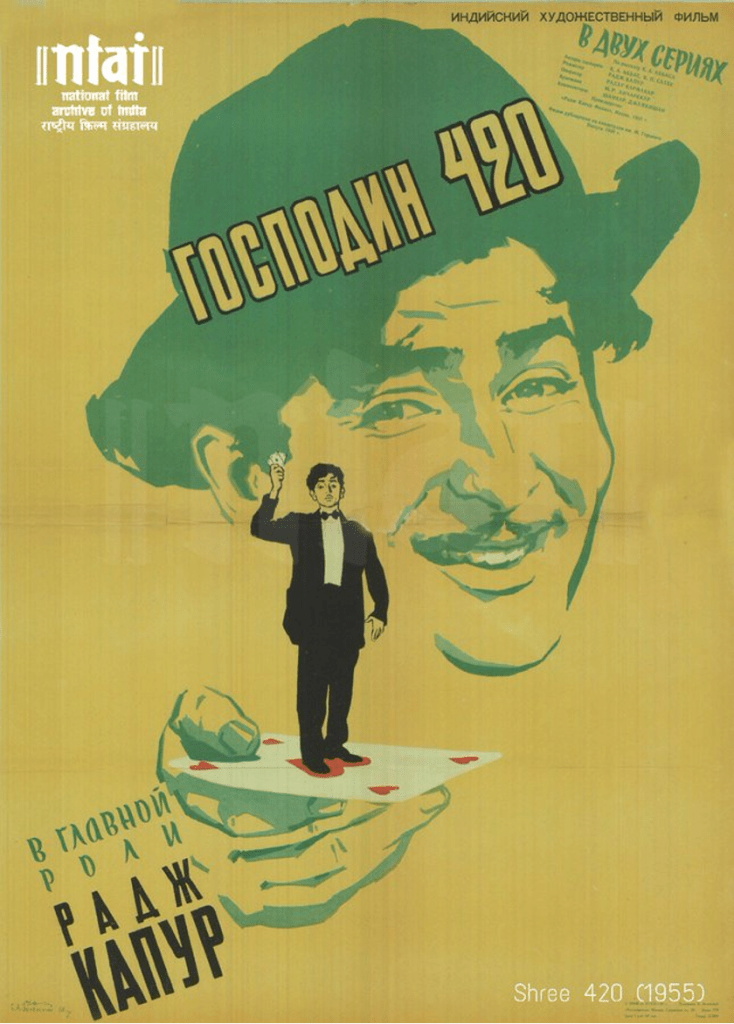

You might have heard about the monumental popularity of Raj Kapoor and other Indian film stars in the erstwhile Soviet Union. This was due to the fact that the prohibition of Hollywood movies and the limited domestic film production compelled the USSR to seek alternative sources of entertainment – turning to Indian cinema, among other things. India’s socialist stance and the themes prevalent in Indian films, such as the portrayal of clear moral contrasts and rags-to-riches narratives, resonated deeply with Soviet audiences.

Just like western films, popular western music was also banned. But western music had been fairly popular in the USSR prior to the Cold War, and people wanted to hear songs they reminisced in their youth. Moreover, the late 1940s and 50s saw the emergence of the stilyagi (Russian for “stylish”). These were members of a youth counterculture movement who were fascinated with modern western music and wore bright foreign-label clothing acquired through the black market, which contrasted with the communist realities of the time. One of the things they were into was vinyl records. Because of their high purchasing power, this led to a lot of illicit businesses for smuggled vinyl records. As these were expensive, the Soviet youth started looking for homegrown alternatives.

PVC was hard to get by in the communist USSR, and its production and procurement, especially for making records, was heavily controlled by the government. This led bootleggers to look for an alternative. It was important to find a substance that met the following requirements:

- It had to be lightweight and malleable like vinyl

- It had to be able to hold grooves on its surface, and

- It had to be easily available.

Soon, the bootleggers had found their jackpot: an unusual substitute that met all the above criteria – X-ray films.

“Bone Music”

X-ray films at the time were highly flammable, and hospitals in communist USSR had to discard all spare films within a year. This prevented a perfect opportunity for bootleggers, who were trying to procure exactly what the hospitals were trying to get rid of. Many would rummage through hospital trash trying to get their hands on as many X-ray films as they could. Some would even go to the back door of the hospital, and procure a bunch of old discarded X-ray films in exchange for a few roubles, or in some cases, a bottle of vodka.

X-ray films were hugely successful for making records. They were convenient to procure and carry around, and could hold grooves once coated with a layer of lacquer. A wax disc cutter and a recording lathe would be used to etch copies of a musical album onto the film, after which they’d be cut using a pair of scissors into a circle. Finally, a hole would be burnt into the centre of the film using a cigarette. And there you had it – an album on an X-ray film that you could play on a turntable!

The sound quality wasn’t fantastic, but it more than just did the job. Much like drugs, these discs were bought and sold in dark alleyways and quiet street corners. Soon, thousands of Russian citizens were able to listen to their favourite music on record players loaded with rotating discs made out of X-ray films. Since chest radiographs are often the most common radiographs taken at hospitals, these recordings were often called “ribs” owing to the distinctive appearance of rib shadows on the covers of these discs. Another term for this kind of illegal music was “bone music,” which came from the radiographs of various kinds of bones as the cover.

This practice soon evolved into an underground business run by black market distributors called “roentgenizdat” (Russian for “X-ray press”). These underground groups made and distributed millions of records before the government started cracking down on them in the 1960s. The 1970s and 80s saw a relaxation of government regulations on record production and distribution, which led to increased availability of vinyl records through official channels. Despite its brief era as a creative workaround, the use of X-ray films for records ultimately gave way to more conventional methods of music production.

If you want to hear how the x-ray records sounded, you can have a sneak peak here!

In its short history, ‘bone music’ had a profound impact on the people of the USSR, particularly in underground music circles and among those seeking access to forbidden cultural expression. These records allowed individuals to circumvent government censorship and listen to the music they loved. Young Soviet citizens would covertly carry these X-ray film records into private parties – illicit gatherings which became havens for cultural rebellion. The secret nature of these gatherings also added an element of excitement and camaraderie, with attendees bonding over their shared love for music that challenged the status quo. In spite of the risks of punishment for possessing or distributing banned records, these private parties were lively places where people exchanged all kinds of music and in their own little way stood up against authority. The impact of these records continues to resonate today as a testament to the human quest for artistic freedom in the face of adversity. Just like how vinyl records hold a special place in the hearts of music aficionados around the world today, records made of X-ray films serve as a nostalgic throwback to bygone eras in the hearts of the people who discovered their enduring passion for music, all thanks to items discarded by the radiology departments of their local hospitals.

Isn’t that simply amazing?

Dr Anmol Dhawan is a radiologist working as a senior resident at Bharati Hospital, Pune. He enjoys writing about radiology, history and culture. You can check out his blog at https://syndrome.home.blog/ and you can reach out to him at anmoldhawan@gmail.com.