Earlier this year, I moderated a Panel on Education and Academics at the Radiology Education Foundation (REF) Leadership Summit held at Mumbai. We discussed various aspects of education, ranging from curriculum and exams, mentorship, accreditation, and improving the quality of teaching and research. One major takeaway was voiced by Sumer Sethi, the founder of DAMS and someone who understands the pulse of this generation very well. He stated that the best way to ensure that something is studied is to include it in the formal curriculum. It is foolhardy to expect residents trained in a system which encourages rote-learning and exam-oriented studies to suddenly learn something important but offbeat that is unlikely to be asked in the exams.

This leads us to the big question. How does one update the curriculum and examination pattern? The National Medical Council (NMC) regulates MBBS, MD and DM training while the National Board of Examinations (NBE) does it for DNB. There will probably be a high-level committee who discusses updates at pre-specified intervals. However, during my journey from giving my MD exams in 2011 to being an MD examiner in 2024, I frankly did not see any major changes.

I am not sure how can one reach out to the board to discuss what are definitely long pending updates to the radiology curriculum and assessment pattern. Nevertheless, I write this blog to create a list of what many would like to see changed, just in case someone in the right place at the right time ends up reading!

Current curriculum and exam pattern:

There is a 12-page 2019 document on the NMC website which lays out the syllabus and the suggested posting schedule across the 3-year MD program. A larger 42-page document on the NBE website does the same for DNB. I could not find details about the date of publishing of the latter, or whether these two are the latest versions of the documents; there is no version control provided in the pdfs.

Overall, the prescribed time spent is about a third each in conventional (x-ray plus fluoroscopy), USG and CT/MRI. MD recommends an even higher time spent in conventional and less in CT/MRI and ultrasound.

With respect to examinations, both MD and DNB exams have four papers which cover specific areas of radiology, along with a practical exam. The MD practical has both internal and external examiners and is usually conducted at the candidates’ parent institute. It would include a few long and short cases, spotters, oral viva voce, table vivas on contrast, instruments, spotters/cases, and a live ultrasound as per the NMC document (the USG is not commonly performed from what I have seen).

The DNB practical exam has only external examiners and takes place in a non-parent institute. It stipulates that the identity of the parent institute of the examinees must not be asked or revealed. It has also become centralized with respect to the spotters, which are common across all institutes and are conducted simultaneously online. It is thus overall a more neutral and systematic assessment.

IS THERE ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT IN THE CURRICULUM?

The best way to create a syllabus is to see how majority of the radiologists currently practice in the real world and ensure that all of the same is covered well during MD/DNB, with the important aspects being evaluated during the exams. This is probably how the original curriculum was designed. Unfortunately, while radiology evolved by leaps and bounds since then, the syllabus has remained relatively static.

Conventional vs current radiology: The original emphasis on conventional radiology, physics, x-ray techniques, and filming made sense earlier as that was most of our work then. However, most practising radiologists spend over 80% of their time reporting CT, MRI, and ultrasound, along with a decent bit of x-ray and perhaps fluoroscopy. They frankly spend 0-1% of their time physically in the ‘dark room’. Thus, the disproportionate prescribed focus on conventional radiology during postings and on x-ray physics during exams is completely out of place today. The candidates certainly need to know how to take a chest x-ray. But is it truly important in the current day and age to know how to take an odontoid or right SI joint view, or the intricacies of film processing?

Newer advances and soft skills: Furthermore, the practice of radiology has evolved substantially in the last few decades. Radiologists now need to be equipped with much more knowledge and skills than in the past, be it on working as a member of a multidisciplinary team, managing a contrast reaction, understanding and using AI (particularly generative AI) in routine practice, and evaluating an original radiology article. All these hard and soft skills need to be formally taught to the residents, to ensure that they are holistically equipped to deal with practical and clinical radiology once they start practicing.

Subspecialty fellowship curriculum and accreditation: Equally importantly, the curriculum for post-MD subspecialty training is not well-defined. Some formal FNB and University recognized structured programs do exist (FNB-certified fellowships need to be two years long, limiting their implementation in radiology). However, majority fellowships are not well defined in their curriculum. As we see more and more institutes offering fellowships, it is important that they get the rigorous focus they deserve. As of now, the lines between a fellowship and a regular SR post are often blurred. This can improve only once the curriculum of a fellowship is better defined and standardized, and fellowships can get accredited / recognized by a University or NMC similar to residency programs.

THE EXAMINATION PATTERN: CAN WE DO BETTER?

While it has stood the test of time, the examination pattern of spotters and long and short cases remains imperfect at best.

Written papers: The four written papers cover physics (paper I), all aspects of radiology from head to toe (papers II and III), and newer advances (paper IV). Paper IV is quite nebulous in its definition, and needs be updated to also include assessing soft skills, knowledge of guidelines and SOPs, and ideally even include an original article for critique so as to assess the students research-related skills.

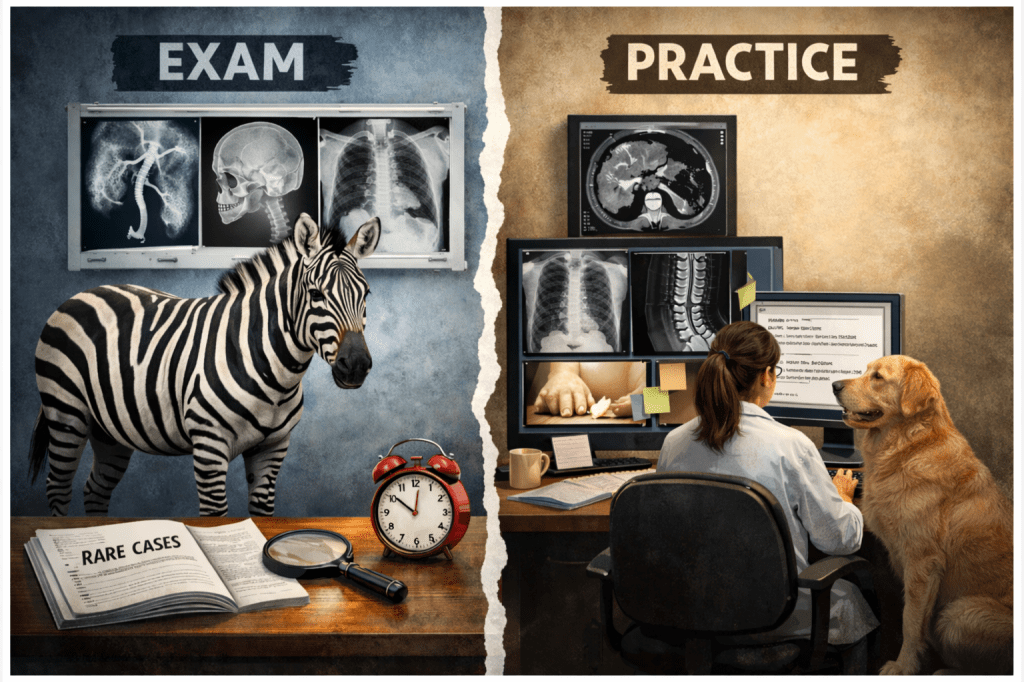

The spotters: The MD/DNB exams generally start with the spotters session. The 30-40 spotters shown cover most radiology subspecialties, and give a broad overview of the overall knowledge of the examinees. While the cases are usually classic, they are often quite rare, and really do not match what we report in routine practice. How often does one report a Caroli’s disease, a cleidocranial dysplasia, a TOF with right-sided aortic arch on chest radiograph, a branchial cleft cyst and X-linked leukodystrophy all in one day, or even a week or a month? More than likely, we may not report even half of the 30 spotter cases in the next 1000 reports we issue in practice.

Furthermore, spotters really do not match how we practice radiology. As Dr Ravi Ramakantan eloquently puts it in this article, ‘in real life radiology, there is never ever a situation where you have to make a diagnosis on a single film in less than 1 min, unless one is a security staff in an airport baggage belt! In real-life radiology, you see contemplation, discussion, and decision.’ We do not issue a report consisting of 1-2 words in routine practice. We may not always give a single diagnosis, but offer a few differentials.

The long and short cases: The cases are overall reasonably fair. They allow sufficient time to assess the images, write a report, present one’s thoughts, and discuss topics related to the case to evaluate the examinee’s knowledge. The presence of only three cases though means that margin for error is low. And if the examinee misses one diagnosis, chances are that the nervousness will make him/her perform badly in all three cases. Furthermore, the cases are often provided as films, while real-life practice is based on DICOM images on an image viewer software. Most residents do not read films anymore and have graduated to something better, and yet their final assessment often happens on an archaic format they are not used to! While this is changing to an extent, this needs to mandatorily become soft copy based.

‘Daily chest’ of cases: If we go back to the basics, the point of the exam is to verify the competence of the radiologist. In other words, if I see a radiology report signed by someone who passes the exam, I as a doctor should be able to trust the report.

And yet, the exam tests less than 5% of what the examinee will go on to report. In real-life, we report many normal studies. We report chest and ICU radiographs, and joint and spine x-rays. We report trauma CTs, acute stroke, bowel obstruction, and pancreatitis, and MRIs for headache, for cervical or lumbar spondylosis, or for knee or shoulder pain. We perform obstetric ultrasound and Doppler studies. These are the studies which form a bulk of our regular cases.

If that is how we practice radiology, why not assess the residents based on this as well? Why have zebras in the exam when we see dogs and cows and horses in actual practice? Certainly, keep some spotters (perhaps 15-20?) for the less common Aunt Minnies, and definitely keep DICOM based long and short cases. But why not also have a ‘daily chest’ of cases, which can be normal and also the garden variety of regular practice. Give 10-20 such cases to each examinee (including normals), give them sufficient time to type their findings and impression, and evaluate them based on the same. This will ensure that residents focus on knowing the basics rather than only on the rare entities and syndromes; that they read about MRI of degenerative spine more than about the findings of myxopapillary ependymoma.

Table vivas: Given the importance of non-interpretative skills in the current era, another option to consider is to define the tables better. We could have one dedicated table for soft skills like contrast reaction management, decision making in complex patients like imaging pregnant or CKD patients, taking consent, tweaking CT and MRI protocols, breaking bad news like IUFD, managing intervention related complications, using generative AI in reporting etc, along with thesis assessment. The other table can be on physics and instruments.

There are many other aspects to consider both with regards curriculum and examination system, which go beyond the purview of this blog. These include:

- Whether MD exams should also be at neutral venues with neutral examiners similar to DNB, and have centrally assessed common spotters and the ‘daily chest’ of cases.

- Should we consider sequential exams (similar to FRCR), with physics (paper I and one table viva) taken at the end of first year, and the rest in final year. The examiners assessing the final MD students can simultaneously assess this for first years.

- Should we introduce a dedicated IR residency pathway for those interested in vascular interventions, instead of the current system of students completing 3 years MD (and often 1 year bond) followed by another 2-4 years in IR as a DM or fellow. One fear of doing so is that this may cause MDs to no longer learn intervention, but one can ensure that the diagnostic MD residency continues to include substantial exposure to non-vascular interventions like biopsies and pigtails, while letting IR residents learn both vascular and non-vascular intervention.

- Is a thesis needed for all MDs or can we give an option to work on a thesis vs something like a Quality Improvement (QI) project.

This is but a small personal list of things which can be tweaked to improve radiology residency and assessment, based on my limited observations. I am sure there are many other aspects which can and should be worked upon as well. I request readers to mention their thoughts and suggestions in the comments section.

– Akshay Baheti, Tata Memorial Hospital